.

How Cannabis Could Influence Appetite

Every time you use cannabis, you probably end the session with your head in the fridge. Thanks to the presence of THC, many cultivars of cannabis ramp up the appetite. But there's more to weed than THC. Other cannabinoids impact appetite in different ways, partly through interacting with the endocannabinoid system—a potent regulator of metabolism.

Contents:

Considering for some that it only takes a few hits from a joint to induce the munchies, it makes logical sense to conclude that cannabis stimulates appetite. Plenty of research also indicates that activation of the endocannabinoid system (ECS) can alter hunger hormones and drive food intake. But the relationship between cannabis and appetite remains complex and nuanced. Different cannabinoids have varying effects on appetite, and both the short-term and long-term use of cannabis affects hunger, energy balance, and metabolism uniquely. Below, you’ll discover the physiology of appetite, how different components of cannabis affect this response, and if the herb can help manage conditions that revolve around an increased or decreased desire to take in calories.

How Appetite Works

Appetite—we wouldn’t last very long without it. But what is appetite? And exactly how does the mass of 30 trillion cells (a.k.a our bodies) convince us to get up and find some calories? Well, it all arises from the homeostatic interplay between specific brain regions, cells throughout the body, and hunger hormones.

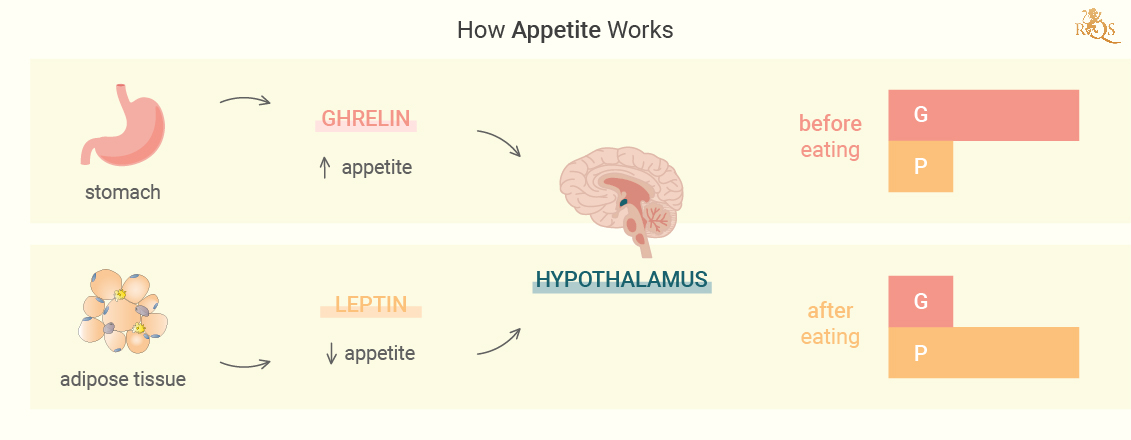

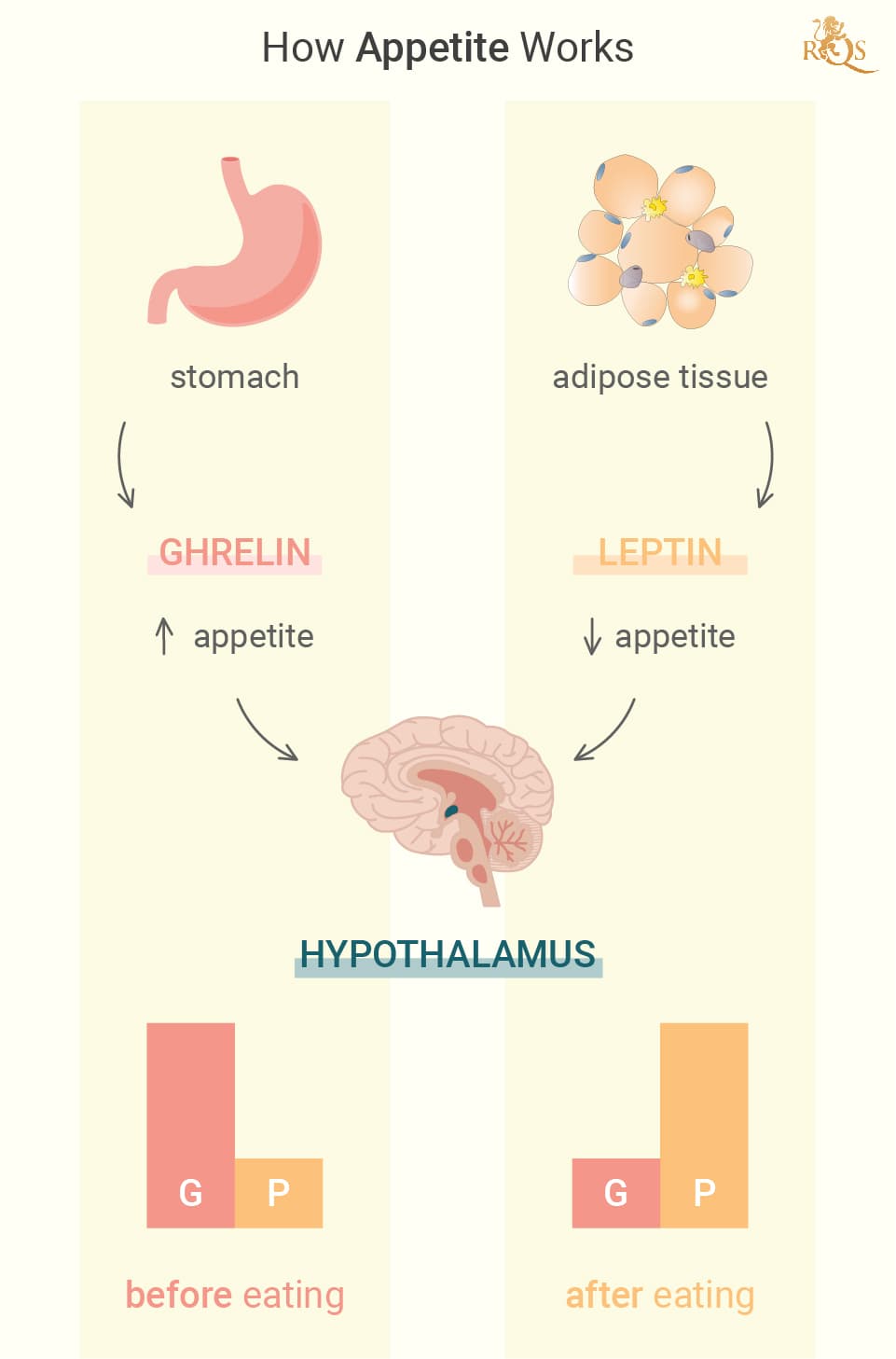

Did you skip breakfast today? Then maybe you felt that growling sensation in your stomach? The rumbling feeling stems from the release of a chemical called ghrelin—a hormone primarily produced by specialized cells that line the stomach. Ghrelin plays many roles in the body, and nutrient sensing[1], meal initiation, and appetite are among these. Following its release, ghrelin enters systemic circulations and makes its way to the brain. Here, it acts on receptors in the hypothalamus, a gland in the brain tasked with controlling the endocrine system and regulating appetite and food intake.

The hypothalamus houses two primary populations of nerve cells that either stimulate or suppress appetite. One of these populations releases hunger-driving proteins known as neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AGRP). The other manufactures hunger-lessening proteins known as cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (AMSH). When ghrelin acts on the hypothalamus, it increases the activity of nerve cells that release the hunger proteins, while dismissing the activity of those that produce hunger-lessening proteins.

This cascade of events seems complex when considering the inner workings of the endocrine and nervous systems. But from an outside view, it involves you putting down a joint and going to grab a burger or reaching out for sweets. But hunger physiology doesn’t stop there. A constant barrage of ghrelin would lead us to keep eating until we do some real damage. In the interest of homeostasis, the signals from the stomach and other organs start to shift as the stomach fills. Ghrelin levels start to drop off. In addition, leptin from fat cells, cholecystokinin from the upper small bowel, and amylin and insulin from the pancreas all influence the hypothalamus to inhibit the feeling of hunger.

Appetite vs hunger

Appetite and hunger are often used interchangeably, but they don’t mean exactly the same thing. Hunger refers to the physiological processes that govern homeostatic eating—all of the cascades of hormones, proteins, and nervous system signalling. We depend on homeostatic feeding for basic metabolic processes and survival.

In contrast, appetite refers to the desire to eat. While appetite often arises from hunger, it also depends on other variables such as stress and emotions and environmental factors. Compared to homeostatic eating, hedonic eating[2] refers to ingesting food based on sensory perception and pleasure, despite metabolic needs already being met. Low appetite also often occurs in patients undergoing chemotherapy, or those that experience eating disorders. Despite the physiological call for hunger, a reduced appetite leads to lower food intake, weight loss, and other issues.

The Endocannabinoid System and Metabolism

The ECS governs homeostasis across many physiological systems in the body, including the skeletal, nervous, and immune systems. And—you guessed it—the ECS also plays a critical role when it comes to energy balance and metabolism. Before we get into just how much sway the ECS holds over these chemical processes, let’s pull it apart a bit.

The classical ECS features three primary components: Receptors, signalling molecules, and enzymes. These include the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2), two major signalling molecules known as endocannabinoids named anandamide and 2-AG, and several enzymes that manufacture and breakdown these endocannabinoids. That doesn’t sound too complicated, right? But it doesn’t end there.

Recently, researchers have expanded the ECS into a larger model labelled the endocannabinoidome[3] that features many more signalling molecules, 20 enzymes, and over 20 receptors. Together, these components help to facilitate many of the ongoing chemical processes in the body that fall under the umbrella of human metabolism. ECS receptors are found in adipose tissue (fat), muscle, liver, and pancreas, and endocannabinoids target these sites[4] to regulate energy homeostasis across the body.

Weed and Food: CB1 and CB2 receptors

Because phytocannabinoids (those derived from plants) and synthetic cannabinoids share a similar structure to endocannabinoids, they’re also able to bind to ECS receptors and cause similar cellular changes and biochemical cascades. Something as simple as tweaking the ECS with these molecules results in different outcomes depending on which are used.

As you know, consuming THC will cause a surge in appetite in most people. Why? Because the cannabinoid binds to the CB1 receptor as an agonist, meaning it raises the activity of the receptor above its baseline. However, there’s a caveat here. Several endocannabinoids found in the body also target CB1 as agonists—resulting in a dysregulation[5] of the ECS that leads to overactivation, which may give rise to an incessant appetite and contribute to states such as obesity.

As researchers started to view CB1 as a promising target for obesity, they set about developing drugs that would interact with the site in a different manner. Inverse agonists of CB1, like the drug Rimonabant[6], have the opposite effect of THC, reducing the activity of the receptor below the baseline. While the drug initially looked successful, it failed due to its scattershot mechanism. By interfacing with CB1 receptors, it also tampered with mood, and many patients experienced psychiatric side effects such as suicidal thoughts.

The CB2 receptor also holds influence over food intake but in an almost entirely opposite fashion. Mouse models[7] show that CB2 agonists, such as the fatty acid palmitoylethanolamide (simply known as PEA), reduced food consumption, whereas the synthetic CB2 antagonist AM 630 increased food consumption.

Cannabis and Appetite

For most, the munchies are a novel, hedonistic, and fun experience. However, the potential of cannabis to modulate appetite spans far past the realm of recreation for many. As research in this field continues to develop, constituents of the herb could offer solutions to those experiencing conditions such as obesity, eating disorders, and medication side effects.

Obesity

The cautionary tale of Rimonabant left researchers cautious when tweaking the ECS with synthetic cannabinoids. However, other natural components of the cannabis plant also display promise in this area. Unlike THC, THCV (tetrahydrocannabivarin) doesn’t produce psychoactive effects because of the way it interacts with CB1. This analogue of THC can behave as both an agonist and antagonist of the receptor depending on the dose. Ongoing animal studies[8] are exploring the molecule as an antagonist of the site to see how it influences appetite, weight loss, obesity, satiety, and the upregulation of energy metabolism.

Eating disorders

The ability of THC and other CB1 agonists to ramp up appetite makes them promising future treatment options in eating disorders such as anorexia. Few human trials have yet tested cannabis for the range of existing eating disorders. However, a 2017 study[9] looked at how THC affects the psychological symptoms of anorexia, including depression and self-reported body care. Additionally, one randomised human trial[10] administered different cannabis products to twenty participants and looked for changes in key hunger hormones such as ghrelin and leptin.

Reducing drug side effects

Various medications also cause a slump in appetite as a side effect. For example, chemotherapy often causes severe nausea and vomiting, the lengthy hospital stays can cause muscle wasting in patients, especially the elderly. Researchers are now exploring the potential of cannabis[11] to increase appetite, body weight, body fat, and caloric intake in such cases.

Is There a Difference Between Eating, Smoking, or Vaping Cannabis?

Does changing the way you use cannabis affect appetite differently? Inhaled and ingested cannabis definitely produce different effects; whereas inhaled cannabinoids have a fast onset and produce less of an intense psychoactive effect, orally ingested weed acts for a longer duration. The conversation of THC into 11-hydroxy-THC also results in a stronger psychoactive effect. Research around which works best to ramp up appetite remains lacking, but some studies[12] are looking into how different routes of administration impact metabolic hormones such as insulin and ghrelin.

What About CBD and Appetite?

We know THC can ramp up appetite, but what about CBD? This cannabinoid doesn’t bind strongly to CB1, but it could influence appetite via other means. Early animal studies suggest that CBD could lead to a reduction in body weight via the CB2 receptor[13]. However, subjective human reports hint that CBD could have the opposite effect and lead to weight gain and increased appetite[14].

Remember when we mentioned the fatty acid PEA above? Well, just like THC is often viewed as the external version of anandamide, PEA is viewed as the endogenous equivalent of CBD. Both of these molecules interfere with ECS enzymes[15] in a way that leads to increased anandamide levels—an endocannabinoid known to activate CB1 and potentially boost appetite.

The Complexity of Appetite, Cannabis, and the ECS

Cannabis constituents work in a very nuanced way in the body. They have to. After all, they’re tweaking and tampering with an overarching and incredibly complex regulatory system in the form of the ECS. Researchers are still getting to grips with how certain cannabinoids impact different parts of the ECS that oversee metabolic functions. While plant components such as THC have a clear impact on appetite, the long-term use of cannabis is actually correlated with weight loss, making things even more confusing for medical cannabis patients looking to stimulate appetite for lengthy periods.

The bottom line: We need more research. Extensive human trials are required to see how different cannabinoids, and different formulas, affect appetite and metabolism. Thankfully, with the increasing acceptance and legalisation of the herb, we’re closer than ever to finding out.

- Ghrelin: much more than a hunger hormone https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Overlapping Brain Circuits for Homeostatic and Hedonic Feeding https://www.cell.com

- The Expanded Endocannabinoid System/Endocannabinoidome as a Potential Target for Treating Diabetes Mellitus https://link.springer.com

- The role of the pancreatic endocannabinoid system in glucose metabolism https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Dysregulation of the endocannabinoid system in obesity https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Rimonabant https://go.drugbank.com

- Behavioral Effects of CB2 Cannabinoid Receptor Activation and Its Influence on Food and Alcohol Consumption https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- The Impact of Δ9-THC on the Psychological Symptoms of Anorexia Nervosa: A Pilot Study https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Effects of oral, smoked, and vaporized cannabis on endocrine pathways related to appetite and metabolism https://www.nature.com

- New Prospect for Cancer Cachexia: Medical Cannabinoid https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Effects of oral, smoked, and vaporized cannabis on endocrine pathways related to appetite and metabolism https://www.nature.com

- Cannabidiol decreases body weight gain in rats: involvement of CB2 receptors https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- A Cross-Sectional Study of Cannabidiol Users https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Palmitoylethanolamide inhibits the expression of fatty acid amide hydrolase and enhances the anti-proliferative effect of anandamide in human breast cancer cells. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov