.

Understanding Cannabis Genetics Terminology

Reading about cannabis genetics can feel overwhelming. Use this list of common cannabis genetics and breeding terms to better understand words like phenotype, genotype, backcrossing, and much more.

Today, thousands of cannabis varieties exist, and breeders around the globe continue to add to the tally. To help you understand what goes into creating the varieties you love most, we’ve created this handy list of cannabis genetics terminology.

Contents:

Understanding Cannabis Strains And Genetics

Cannabis autumns into the category of a dioecious plant. This means that individual plants have either male or female reproductive organs, not both. Female plants grow flowers that develop glandular trichomes—structures that produce phytochemicals such as cannabinoids and terpenes. Male plants possess small sacs that release pollen to fertilise female plants.

However, cannabis plants can sometimes be monoecious, meaning both male and female sex organs emerge on the same plant. This occurs due to either genetic or environmental factors, and ultimately allows a plant to fertilise itself. Known as hermaphroditism, it serves as an impressive reproduction mechanism for stressed plants, yet most growers try to avoid this phenomenon as it causes their flowers to produce seeds.

Cannabis is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the Cannabaceae family (which also comprises hops and other plant species). While cannabis grows all over the world, it is believed to originate from Central Asia, which is also likely where it was first domesticated.

Besides being dioecious, cannabis plants can be further divided into three distinct subspecies; Cannabis sativa (C. sativa subsp. sativa), Cannabis indica (C. sativa subsp. indica), and Cannabis ruderalis (C. sativa subsp. ruderalis), all of which have unique traits:

| Cannabis sativa | These plants originate from warmer, tropical climates. They typically have longer flowering times and grow taller with large internodal spacing. Sativas tend to produce large, airy buds that can stand up to warm, humid conditions. |

| Cannabis indica | Indicas originate from colder regions in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. They grow shorter and bushier, have shorter flowering periods (as they adapted to the shorter summers in these regions), and typically produce more dense buds than sativas. |

| Cannabis ruderalis | Discovered in Russia in the 1920s, ruderalis plants grow very small, typically reaching maximum heights of 60cm, and develop thin, slightly fibrous stems with few branches and flowers. Unlike Cannabis sativa and indica, which flower based on changes to their photoperiod, ruderalis plants begin to flower automatically once they are about 4 weeks old. |

| Cannabis sativa |

|

These plants originate from warmer, tropical climates. They typically have longer flowering times and grow taller with large internodal spacing. Sativas tend to produce large, airy buds that can stand up to warm, humid conditions. |

| Cannabis indica |

|

Indicas originate from colder regions in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent. They grow shorter and bushier, have shorter flowering periods (as they adapted to the shorter summers in these regions), and typically produce more dense buds than sativas. |

| Cannabis ruderalis |

|

Discovered in Russia in the 1920s, ruderalis plants grow very small, typically reaching maximum heights of 60cm, and develop thin, slightly fibrous stems with few branches and flowers. Unlike Cannabis sativa and indica, which flower based on changes to their photoperiod, ruderalis plants begin to flower automatically once they are about 4 weeks old. |

A Note on Hemp

People often confuse hemp as a separate species of cannabis. However, hemp is just a term used to refer to cannabis varieties that have been bred for industrial purposes, such as to produce fibre for textiles. Hemp plants typically have very low concentrations of THC and produce big, thick stems and few branches.

Understanding Cannabis Genotype and Phenotype

The difference between genotype and phenotype is a fundamental concept you need to wrap your head around in order to properly understand cannabis genetics.

| Genotype | This refers to a cannabis plant’s genetic composition, or the combination of genes passed down from its parents. These genes serve as a code for the potential traits a plant might express, including characteristics such as height, internodal spacing, colour, and leaf shape. Overall, think of genotype as the instructions for all of the potential traits a plant could develop based on the genetic information inherited from its parents. |

| Phenotype | Whereas genotype is all about genetic instructions, phenotype refers to the combination of traits a plant actually expresses as it grows. Phenotype is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. |

| Genotype |

|

This refers to a cannabis plant’s genetic composition, or the combination of genes passed down from its parents. These genes serve as a code for the potential traits a plant might express, including characteristics such as height, internodal spacing, colour, and leaf shape. Overall, think of genotype as the instructions for all of the potential traits a plant could develop based on the genetic information inherited from its parents. |

| Phenotype |

|

Whereas genotype is all about genetic instructions, phenotype refers to the combination of traits a plant actually expresses as it grows. Phenotype is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. |

Cannabis Phenotype vs Genotype: Example

Genotypes are determined by the genes a plant inherits from its parents. Each gene can present two or more alleles, which are variant forms of a gene that differ in DNA sequence and carry information that code for different traits. The children of a human couple, or seeds of a plant, can carry different alleles despite having the same parents. For example, two children born of the same parents may have a different eye colour. The same applies to cannabis seeds. After crossing a female with a male, breeders end up with seeds that possess genetic variations.

As an example for growers, two seeds from the same parents have two different genotypes. This means they’ll display slightly different traits even when grown under the exact same conditions.

How does this differ from a phenotype? Well, phenotype describes how a plant looks and behaves; i.e. how the genotype interacts with the environment to determine a plant’s traits.

Let’s say you’ve just sown a packet of seeds from the same parents. Throughout the growing cycle, you treat them all exactly the same. You give them all the same soil, nutrients, water, pot size, and light exposure. Despite the strict environmental conditions, you’ll still notice subtle differences between each plant come harvest time. That’s because each of them features a distinct genotype.

Many breeders use phenotype selection to produce new strains. By selecting the plants that grow the best in the same environment, they can tease out desired traits over subsequent generations. Remember, a phenotype depends on both genes and the environment, not genes alone. Therefore, even clones (which share the same genotype) can develop different phenotypes based on external conditions. For example, placing two different cuttings from the same plant at different distances from a light source will affect their height.

Cannabis Genetics Dictionary: Understanding Genetics and Breeding Terminology

Now that you have a solid understanding of the basic principles of cannabis genetics, here is an overview of some terms used to describe different cannabis varieties.

Chemovar / Chemotype / Cultivar / Strain

You may have noticed people in the cannabis space interchanging the terms chemovar, chemotype, cultivar, and strain.

Although they’re all related, there are some important distinctions to consider.

1. Chemovar and Chemotype

These terms are often used interchangeably, and reference a method of categorizing strains based on their dominant cannabinoid(s)—and more recently, their secondary cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids. The three main chemotypes are THC-dominant, CBD-dominant, and balanced CBD:THC varieties.

2. Cultivar vs Strain

The term cultivar refers to a cultivated plant variety. Essentially, it refers to plants that humans have grown and interfered with to “better them” for a particular purpose. Most of the vegetables and fruit we buy at the supermarket come from specific cultivars that have been bred to produce large yields, for example.

“Strain”, on the other hand, is most commonly used in virology and microbiology to refer to the genetic variance of microorganisms such as viruses and bacteria. While it is also commonly used to refer to genetic variance in cannabis, the correct term would be “cultivar”, seeing that cannabis has long been cultivated and bred by humans for a variety of purposes.

As our understanding of cannabis grows, using the right terminology to describe different types is extremely important. At RQS, we think it is vital to demystify cannabis lingo and begin adopting terms like chemovar and cultivar to refer to the cannabis varieties we’re growing and breeding, rather than solely using outdated terms like sativa, indica, or strain.

Stabilisation

Genetics is the study of genes, which are made up of segments of DNA that essentially lay down the foundations for the traits a plant might develop. Cannabis plants, like many other organisms, may express alternative versions of a specific gene (known as alleles). The expression of different alleles is what causes plants to develop different traits and grow into different phenotypes.

Stabilising cannabis involves using breeding techniques to create cultivars with less allelic diversity (or versions) in their genes. Over time, this produces stable plants that express more uniform traits, ultimately resulting in a more consistent and reliable product (seeds) for growers.

Purebreds and Landraces

Today, calling a cannabis variety “pure” is pretty misleading. The truth is that cannabis has been vigorously crossbred over (at least) the last 40 years by humans, and likely for thousands of years before that by nature itself (in nature, a single male cannabis plant is capable of pollinating females many kilometres away). So for a grower or breeder to refer to a particular cultivar as a "pure breed" is pretty obnoxious.

The term landrace is also pretty polemic. Growers and breeders use this to refer to cannabis varieties that developed in their natural environment and were never crossed with any other foreign variety. While landrace cannabis varieties definitely existed in the past, whether they are still around today is debatable. We highly recommend checking out the Phylos Galaxy[1] for an impressive visual display of the complexity of the cannabis gene pool, and how varieties have been meticulously crossbred for decades, and even centuries.

Heirloom Varieties

Heirloom is a horticultural term used to refer to primitive cultivars that are open-pollinated and not used widely in agriculture. Heirloom varieties typically also haven’t been genetically manipulated or otherwise interfered with.

If you were to fly to the Himalayas, track down an heirloom cannabis variety growing naturally in the region, take a clone from that plant, and continue to grow that same plant in your bedroom in Barcelona, for example, that plant would be considered an heirloom cannabis cultivar.

Crossbreeding

Crossbreeding refers to the act of taking one cannabis cultivar and crossing it with another. The simplest way to do this would be to take pollen from a male cannabis plant and use it to pollinate the flowers of a female plant. These plants would then be considered “parents” of the resulting crossbreed.

Inbred Lines (IBLs)

Selfing marijuana cultivars are obtained by using parent plants with predictable traits. This results in a high degree of homozygosity—the state of possessing two identical alleles for a particular gene, one from each parent. Breeders achieve this by inbreeding—either "selfing" the plant or crossing two plants of the same genotype. Selfing refers to a technique where breeders force a plant to become a hermaphrodite and breed with itself. Such stable genetics are often found among wild landrace populations of cannabis that breed in isolation for long periods of time.

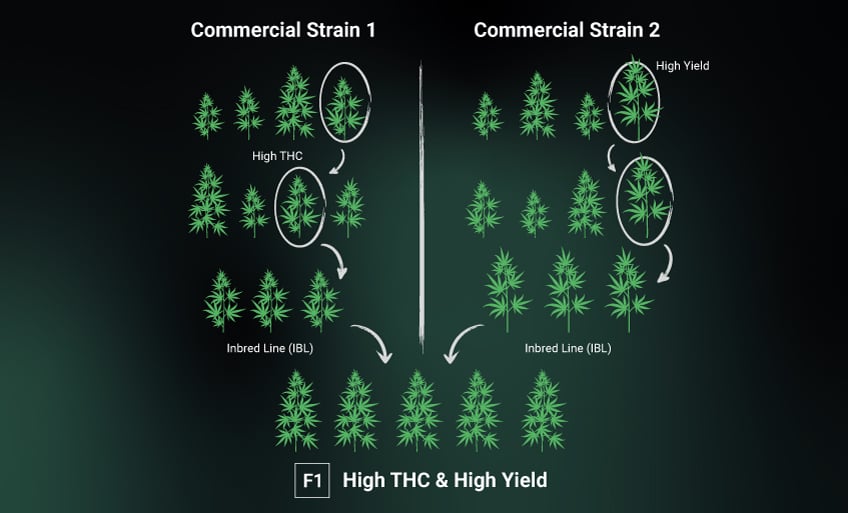

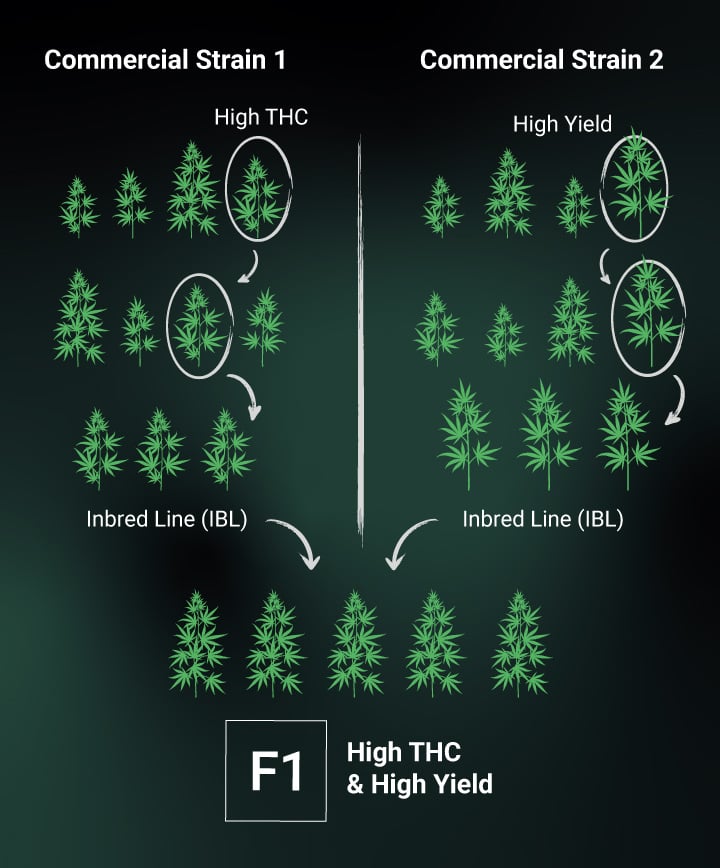

F1 Hybrid

The term F1 stands for “filial 1” and refers to the first line of offspring produced by crossing two inbred lines. For example, if you used an inbred line of Royal Gorilla males to pollinate an inbred line of Sherbet Queen, the resulting plants would be considered F1 hybrids. Because of the genetic stability of the parents, the progeny would also display consistency and uniformity.

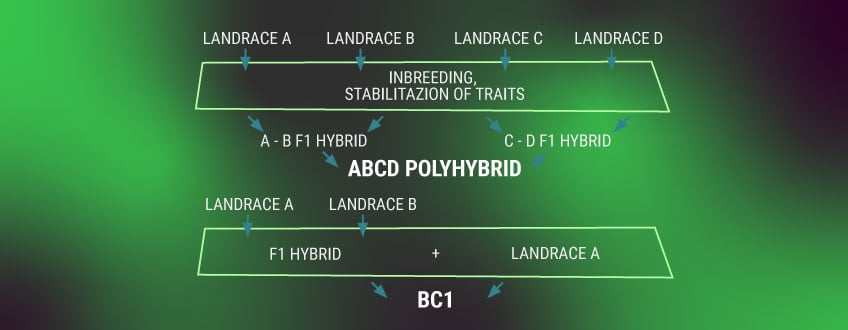

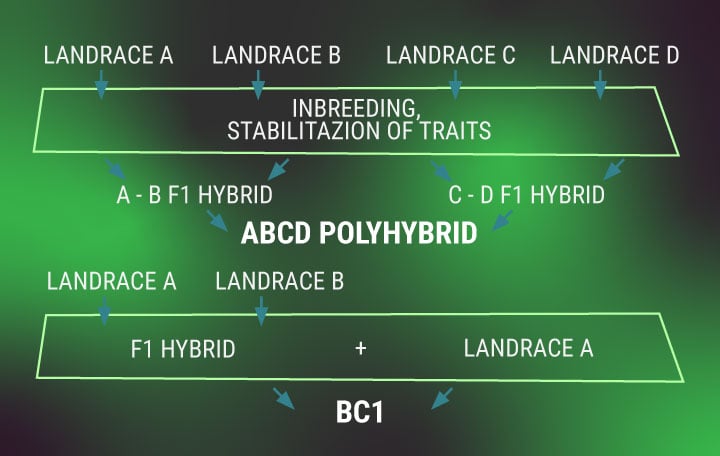

Polyhybrids

Polyhybrids are cannabis varieties bred from the crossing of two F1 hybrids. Polyhybrids have more genetic variation than F1 hybrids, as they are composed of four IBLs. Normally, polyhybrids are used when hybrid seed production is low in the inbreeding lines. When two F1 hybrids are crossed, the seed production is higher due to the hybrid vigour.

Backcross (BC)

Cannabis breeders use backcrossing to introduce a specific trait to a variety, such as resistance to a certain pest. This involves crossing a first-generation hybrid plant with a clone of one of its parents. In essence, backcrossing helps to diminish alleles from one parent and stabilise specific traits from the other parent.

Backcrossing helps to eradicate bad traits and fix the desirable ones. By crossing a progeny with one of its parents, the new offspring will feature the genetic background of one parent and the interesting gene/genes from the other. This strengthens the traits sought after by the breeders, and increases the likelihood of them appearing more abundantly in future generations.

Backcrosses are usually labelled BC1, BC2, BC3, etc., with the number reflecting the generation of the cross.

S1

S1 is a term used to describe the first generation of cannabis seeds produced by crossing a cannabis cultivar with itself. While there are different ways to do this, most breeders use stress to force a female plant into producing pollen and pollinating itself—a process known as “selfing”.

Cannabis Genetics Demystified

The wide world of cannabis genetics can be hard to understand. Whether you’re looking to start breeding your own cultivars or just want to have a deeper understanding of cannabis and what goes into creating the varieties you love most, make sure to keep this list handy!

- The Phylos Galaxy https://phylos.bio